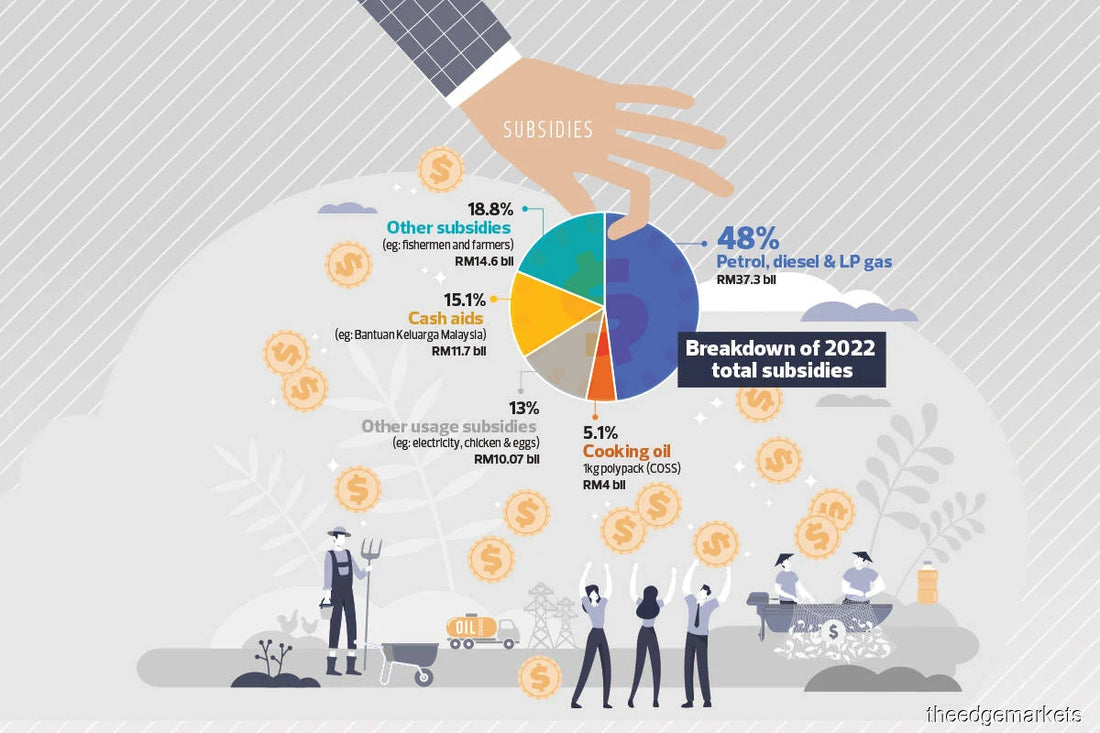

Special Report: At RM77.7 bil, subsidies exceed budgeted development expenditure in 2022

JUST as recession-related fears sent Brent crude futures below US$100 per barrel for the first time in three months and sparked a debate on whether there are indeed grounds for substantial declines in the coming months, Finance Minister Tengku Datuk Seri Zafrul Aziz told the media on July 7 that the government is testing mechanisms to determine how best to execute targeted fuel subsidies.

What’s certain is that Malaysia’s projected total subsidies bill of RM77.7 billion (as at June 29) will exceed the planned development expenditure of RM75.6 billion budgeted for 2022 last November — if Brent crude oil continues to hover above US$100 per barrel this year, essential food prices remain high and blanket subsidies remain in place.

This isn’t the first time this has happened, but more on this later (see Chart 1).

Almost RM20 billion of the RM37.3 billion fuel subsidy may be going to the better-heeled (and better-wheeled) populace — including foreigners pumping subsidised RON95 fuel and diesel at the local petrol station — based on Zafrul’s statement in May that 53% of fuel subsidies goes to the top 20% of households (T20) compared with just 15% for the bottom 40% (B40). Conversely, only RM5.6 billion of the expected spending this year would benefit people riding kapcais and driving smaller locally made cars who are more deserving of government aid. That fact alone makes it hard for policymakers to ignore the merits of targeted fuel subsidies.

Almost RM20 billion of the RM37.3 billion fuel subsidy may be going to the better-heeled (and better-wheeled) populace — including foreigners pumping subsidised RON95 fuel and diesel at the local petrol station — based on Zafrul’s statement in May that 53% of fuel subsidies goes to the top 20% of households (T20) compared with just 15% for the bottom 40% (B40). Conversely, only RM5.6 billion of the expected spending this year would benefit people riding kapcais and driving smaller locally made cars who are more deserving of government aid. That fact alone makes it hard for policymakers to ignore the merits of targeted fuel subsidies.

After all, RM20 billion is more than the amount spent on education (RM8.23 billion) and health (RM8.72 billion) put together under development expenditure in 2021. It is also more than the RM16.16 billion disbursed under the Bantuan Prihatin Nasional (BPN) cash transfer in 2020 that benefited 10.6 million households and individuals.

At RM77.7 billion, chances are that the subsidies and cash assistance bill will exceed 25% of federal government revenue this year and likely necessitate at least RM15 billion more in dividends from government-linked institutions even after taking into account larger commodity-related revenues due to a commitment to keep fiscal deficit near 6% of GDP, our back-of-the-envelope calculations show (see Chart 2). Petroliam Nasional Bhd (Petronas) has committed to pay RM25 billion and the highest to date was RM54 billion in 2019 due to a special dividend of RM30 billion to pay back excess tax owed to businesses and individuals. It is understood that about RM31 billion (of the RM77.7 billion) has been accounted for in Budget 2022.

At RM77.7 billion, chances are that the subsidies and cash assistance bill will exceed 25% of federal government revenue this year and likely necessitate at least RM15 billion more in dividends from government-linked institutions even after taking into account larger commodity-related revenues due to a commitment to keep fiscal deficit near 6% of GDP, our back-of-the-envelope calculations show (see Chart 2). Petroliam Nasional Bhd (Petronas) has committed to pay RM25 billion and the highest to date was RM54 billion in 2019 due to a special dividend of RM30 billion to pay back excess tax owed to businesses and individuals. It is understood that about RM31 billion (of the RM77.7 billion) has been accounted for in Budget 2022.

Apart from 2008 (the year of the 12th general election), official data for the past two decades show headline subsidies have only risen above 20% of federal government revenue in 2011, 2012 and 2013, when Brent crude prices averaged above US$100 per barrel, like what is currently expected for 2022 (see Chart 3). To be sure, fuel subsidies are extraordinarily high this year because of the high global oil prices. It is also because the current price ceiling for RON95 petrol of RM2.05/litre and diesel of RM2.15/litre (since February 2021) is lower than the previous price ceiling of RM2.08/litre for RON95 and RM2.18/litre for diesel implemented in 2019. For comparison, the unsubsidised RON97 petrol was retailing at RM4.84/litre at the time of writing.

Apart from 2008 (the year of the 12th general election), official data for the past two decades show headline subsidies have only risen above 20% of federal government revenue in 2011, 2012 and 2013, when Brent crude prices averaged above US$100 per barrel, like what is currently expected for 2022 (see Chart 3). To be sure, fuel subsidies are extraordinarily high this year because of the high global oil prices. It is also because the current price ceiling for RON95 petrol of RM2.05/litre and diesel of RM2.15/litre (since February 2021) is lower than the previous price ceiling of RM2.08/litre for RON95 and RM2.18/litre for diesel implemented in 2019. For comparison, the unsubsidised RON97 petrol was retailing at RM4.84/litre at the time of writing.

While politicians, who will need to face the ballot box within the coming year, may well be inclined to kick the barrel down the road — some may even cite Citi’s July 5 projections of Brent crude tumbling to US$65 per barrel by year end if an “increasingly likely” recession hits the global economy and cool to US$85 per barrel even without a recession — the coalition that wins Putrajaya will need to replenish government coffers that depleted during the Covid-19 pandemic to have greater fiscal flexibility to battle future challenges. It would be easier to remove blanket subsidies from consumers when prices are low but immediate government savings would also be low.

When Brent crude last averaged above US$100 per barrel in 2011 to 2013, subsidies for petrol, diesel and liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) were between RM20.4 billion (2011) and RM27.9 billion (2012), according to publicly available federal budget-related documents for 2010-2015, which provided a breakdown of what was spent annually on subsidies for petrol, diesel and LPG instead of a more generic “subsidies and cash assistance” since 2016 (see Chart 4).

With Brent crude averaging US$104 per barrel year to date at the time of writing, subsidies for petrol, diesel and LPG alone are projected to triple year on year to RM37.3 billion — about triple the RM13.2 billion for 2021 when Brent crude averaged US$77.8 per barrel and 23 times the RM1.6 billion for 2020 when Brent crude averaged US$51.8 per barrel and many had spent time at home amid the pandemic.

According to the Ministry of Finance’s (MoF) June 25 statement, subsidies for petrol, diesel and LPG alone came to RM7.4 billion in 2018 (Brent crude averaged US$53.8 per barrel) and RM6.1 billion in 2019 (Brent crude averaged US$66 per barrel).

Zafrul’s statement on the rich being the largest beneficiaries of blanket subsidies is not new. In 2014, researchers at Bank Negara Malaysia found that 42% of fuel subsidies could be going to the T20 compared with only 4% going to the bottom 20% (B20). This is consistent with findings in a 2010 working paper by the International Monetary Fund on global fossil fuel subsidies, where researchers found the poorest 20% getting only 7% of subsidies while 43% went to the richest 20%.

MoF did not give previous years’ figures for an apple-to-apple comparison of the RM77.7 billion in subsidies and social assistance for 2022 in its June 25 statement (see Table 1). What’s clear, though, is that the headline “subsidies and social assistance” amount listed under operating expenditure in the federal government’s annual budget — RM19.8 billion in 2020 (actual), RM23.04 billion in 2021 (actual) and RM17.35 billion in 2022 (budgeted) — is not the total amount the government spends on subsidies and social assistance (see Table 2).

It is also clear that blanket fuel subsidies are taking up billions that may well be better spent on other areas of development. It is hoped that policymakers will do more than just talk about high subsidy bills and actually take more concrete steps towards implementing what’s right, as well as communicate to the people how targeted subsidies will actually work better for the nation as a whole in the long run.

Source: The Edge Market